The Vulture Chronicles: Of trains, birds, parathas and camaraderie

Munir Virani

It’s about 11.30 at night and I am standing on Platform 2 at Umaria train station, in the heart of the state of Madhya Pradesh in Central India. It’s not as bitterly cold as in previous years and yet the cold night air wraps itself around us like a blanket. There is the deep resonant hum of a distant train that echoes through the valley. It’s a strange juxtaposition—modern railways cutting through a landscape steeped in ancient history. My colleagues from The Corbett Foundation and I, huddled together for warmth, are about to embark on the second leg of our journey to Rajasthan. Our train is 40 minutes late and my eyes are heavy. Sleep seems to be far in the distance. My excitement has reached fever-picth – I will be visiting my old stomping grounds there after a hiatus of eight years. The mood is buoyant, fueled by the camaraderie of shared purpose and the sheer privilege and honor of having spent the last few days immersed in the wonder that is Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve. Yet, amid this atmosphere of determination and excitement, there is also a solemn pause in our hearts tonight. One of our drivers, Surjit, lost his father earlier this evening. We take a moment to dedicate this article to his memory—a gesture of respect and honor for Surjit’s strength and dedication in continuing with us despite his loss.

Nestled in the heart of Madhya Pradesh, Bandhavgarh is renowned for its dense tiger population, but its significance extends far beyond its iconic predators. This park, with its sweeping landscapes of sal forests, open meadows, and towering cliffs, harbors a treasure trove of biodiversity. It is also a crucible of human history and mythology, its centerpiece being the ancient fort perched atop the highest hill. This fort is no ordinary relic—it is said to have been gifted by Lord Rama to his brother Lakshmana, and its walls still whisper stories of gods and demons. It is here, according to legend, that Jatayu, the vulture god, heroically raised the alarm when he witnessed the demon Ravana abducting Sita. In his sacrifice to warn humanity, Jatayu’s fate mirrors that of his real-life counterparts today—vultures, guardians of the ecosystem, now paying the ultimate price due to human negligence.

The decline of vulture populations in South Asia, primarily caused by the veterinary drug diclofenac, is one of the most tragic and pressing conservation crises of our time. Once numbering in the millions, these majestic scavengers have seen populations plummet by over 90% in just a few decades. Diclofenac, used to treat livestock, is lethal to vultures feeding on the carcasses of treated animals. This catastrophic loss has unleashed a cascade of ecological consequences, from increased prevalence of rabies to disrupted food chains. Yet, as we have seen over these past days in Bandhavgarh, the numbers of soaring vultures are yielding hope that persists in the form of dedicated monitoring and conservation efforts by a cadre of committed individuals and organizations.

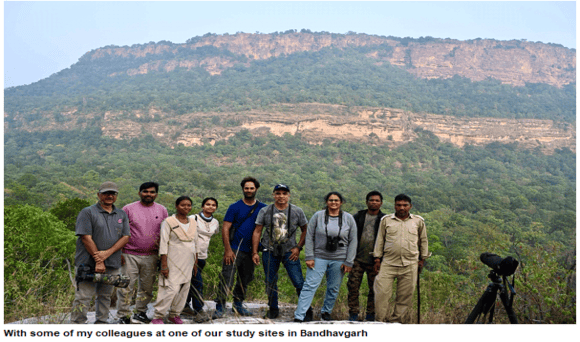

Each day over the period we were there, our days in Bandhavgarh usually began at the crack of dawn, with tea in hand and mist rising over the forest floor. Surjit and Iqbal, our illustrious drivers were always on time to pick us up, their smiles adding more light to the early morning rays of sunshine. Each day brought its own sense of wonder and discovery. Driving through the park’s winding roads, we saw spotted deer darting across our path, peacocks displaying their iridescent feathers, and the occasional barking deer or Malabar pied hornbill perched high in the canopy. The forest, still lush from the monsoon rains, enveloped us in a symphony of birdcalls—rufous treepies, rose-ringed parakeets, flameback woodpeckers, and kingfishers among them. We watched as vultures bathed cautiously in one of the dams under the watchful eye of a stunning Crested Hawk-eagle. Butterflies flitted through sunbeams, and dragonflies skimmed the surface of watering holes. It was a sensory feast, but we were here with a mission: to document the nesting sites and population health of the critically endangered Indianvultures, a study that we are building on after a hiatus of eight long years. Reaching the iconic Dolphins Head, a rocky precipice overlooking one of the park’s largest cliffs, was both a physical and emotional journey. Cutting through thorny underbrush and climbing through thick vines, we finally arrived at this stunning vantage point, our telescopes and datasheets in hand. The wind carried the sound of wings—a mesmerizing, whooshing rhythm as vultures soared past us. We watched in awe as these magnificent birds glided effortlessly, their wings catching thermals with grace, was a humbling experience. We meticulously recorded data, each alphanumeric nest site a testament to the persistence of life in the face of adversity.

The fort itself, shrouded in mist and history, was a marvel. As we entered its ancient gates, the cries of bats echoed through its chambers, a haunting reminder of its layered past. Amid the towering walls and man-made dams that have withstood two millennia, the sacrifices of Jatayu felt especially poignant. Today, the vultures of Bandhavgarh continue to fight for survival, their plight symbolic of the urgent need to protect the delicate balance of our natural world. Our days were filled with challenges—long treks through tiger territory, navigating dense forests, and enduring bites from ticks and fire ants. Yet, the rewards far outweighed the hardships. A shared meal of spicy potato curry and parathas, a laugh over a cup of chai, and the unspoken bond of working together for a cause greater than us all underscored the joy of being part of this effort.

As we board the midnight train to Kota, I reflect on the journey so far. Nearly a quarter of a century has passed since I first set foot in Bandhavgarh, yet the forest’s allure remains undiminished. The vulture surveys, conducted in partnership between the Mohamed bin Zayed Raptor Conservation Fund and the Corbett Foundation, are a continuation of the late Sheikh Zayed’s vision of conservation as a shared global responsibility. It is an honor to contribute to this legacy, to stand alongside our partners in India – the Corbett Foundation, and to remain a witness to the resilience of nature and the warmth and smiles of the Indian people.

I must emphasize that this journey is not just about counting vultures and their nests; it is about honoring their role as sentinels of the ecosystem and advocating for coexistence. In their silent, soaring grace, they remind us of the interconnectedness of all life and the sacrifices necessary to sustain it. As the train pulls away from the station, I am filled with gratitude—for the forests, the birds, and the people who make this work possible.

Leave a reply