Giants of India's Conservation Legacy: A Farewell to Remember

Munir Virani

My field expedition in India ended just as fast as it had started. I was there under my new role at the Abu Dhabi based Mohamed bin Zayed Raptor Conservation Fund, dedicated to the conservation of threatened raptors worldwide. I was in India with a team from the Corbett Foundation that we have partnered with to build and expand on enhancing efforts to conserve the critically endangered Indian Vulture (previously called Long-billed Vulture). I was visiting my old stomping grounds after a hiatus of eight years and I could not have asked for better colleagues to be with. My head was a whirlwind of memories, colours, tastes and smells combined with the spectacular array of birds and animals that remain tattooed in my head. I was in Jaipur, the pink city of India, home of Maharajas, palaces, colours, flavours and music. This was my last stop before flying back to Abu Dhabi. As the sun began to set on my final day in Jaipur, I felt the presence of regal history with vibrant echoes of conservation. I was very excited for I was to meet with two towering figures in India’s conservation narrative: Mr. Harsh Vardhan and Dr. Divyabhanusinh Chavda. Both these individuals have had an enduring dedication to the conservation of India’s wildlife and natural heritage. More importantly, both of them have profoundly influenced my personal career in conservation.

Mr. Harshvardhan, the Secretary and founder of the Tourism and Wildlife Society of India, is not just a guardian of nature but a catalyst for change, a connector. I met Harsh for the first time in Jaipur 24 years ago and he welcomed me with open arms and introduced me to the beauty and complexities of India’s wildlife conservation, setting me on a career path in raptor conservation. Seeing Mr. Harsh Vardhan again after many years was an emotional reunion. As he welcomed me into his home, I felt the warmth of his presence – it was a comforting embrace. It reminded me of our first meeting decades ago. His house, a repository of artifacts, paintings, photographs and manuscripts, spoke volumes of his life’s work. Despite the recent, immense personal loss of his dear wife, his spirit remained unbroken, his hospitality boundless, his humour enchanting. The ambience at his home was thick with memories and respect, further enriched by the presence of his son, Manoj, his daughter-in-law, and his two handsome grandsons, and Bosco, their daschund. Their respectful and obedient demeanor reflected the deep-rooted values and rich cultural heritage of their family. I was filled with joy and admiration. We dined together, indulging in a traditional Rajasthani feast that was as rich in flavor as it was in tradition. The meal was made up of succulent bafla, a hearty dish made from millet, served alongside a deliciously spiced eggplant curry and a comforting lentil soup. Each morsel in my mouth was a testament to the Rajasthan’s culinary heritage that I have become so familiar with for over a quarter of a century. And yet, the flavours exploded in my mouth – I had been eating restaurant food for nearly three weeks and this home-cooked meal (with love) felt like paradise. I sat at this very table 25 years ago and it was as if time had stood still. This was not just a place for eating but a “majlis” (meeting place) for reconnecting, as we reminisced over the challenges and triumphs of past conservation efforts, rekindling the deep connection forged by years of shared ideals and mutual respect. The emotional pinnacle of the evening came was when Mr. Harsh Vardhan presented me with a copy of his book on the Great Indian Bustard. Holding the book, a culmination of his dedication and hard work, I was nearly moved to tears. I hugged Harsh very tightly – In India, this is known as “Jadoo ki Jhappi” (a magical hug to someone special who deserves great appreciation). It was a reminder of our enduring bond and the shared commitment to conservation that had initially brought us together. This book and other gifts he gave me, like the evening itself, was not just an exchange of tokens but a renewal of our lifelong dedication to the cause we both hold dear.

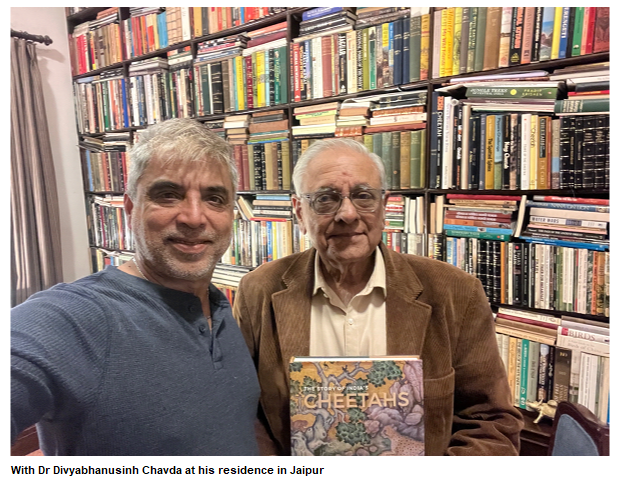

The following day, my visit to Dr. Chavda’s residence was nothing short of stepping into a historical trove of conservation literature. Dr. Divyabhanusinh Chavda’s presence exudes a regal aura, his scholarly pursuits anchored in his profound contributions to wildlife research. His focus on the Asiatic Cheetah has a carved a path for their hopeful return. His office, a grand room lined with an impressive collection of (I kid you not) over 5,000 books, was a sanctuary of knowledge, a space that seemed to capture the essence of his lifelong dedication to wildlife conservation. Dr. Chavda, dressed impeccably in a blazer that hinted at his regal background, exuded a class that transcended his attire. His eloquent knowledge and experience on the plight of the Asiatic cheetahs and lions, and his strategic insights into their conservation, were as enlightening as they were inspiring. Over a cup of tea, we delved deeper into our conversation. Dr. Chavda shared his extensive knowledge on an aspect of conservation that I knew very little about: the historical role of cheetahs in Indian falconry. I sat there in awe and admiration, and he told me how he had access to medieval falconry manuscripts in Persian, documents that have not yet been translated but hold a wealth of information about the practices and traditions of falconry in historical India. His passion for these manuscripts and their potential to shed light on a lost heritage was palpable. Dr. Chavda had a deep interest in the interconnected histories of cheetahs and falconry, emphasizing the cheetah’s role not just as a hunted species but as a hunter, integrated into the cultural fabric of Maharaja hunts.

During our discussion, Dr. Chavda lamented the profound changes in the Indian landscape, reflecting on his own experiences with wildlife, “Not long ago, I used to shoot partridges right outside my doorstep,” he remarked, his tone a mixture of nostalgia and sorrow for a time when wildlife was a more common sight in daily life. This personal anecdote mirrored his deep-seated concerns about habitat loss and the dramatic transformations he has witnessed over the decades. Speaking with Dr. Chavda in Gujarati, our native tongue, added a layer of personal connection to our discussion, making the complex topics more intimate and poignant. His ability to articulate complicated conservation issues in such a familiar language brought an emotional depth to our conversation, bridging the gap between scholarly research and heartfelt dialogue. When Dr. Chavda gifted me his most updated book on the cheetah, I felt a profound sense of gratitude, continuity and hope. Holding the culmination of his life’s research in my hands, I was more inspired than ever to continue with my own research. The book was an inspiration to both the past struggles and future possibilities of conservation in India. Dr Chavda insisted on dropping me back to my hotel and as I left his study, I was inspired by his scholarly achievements and his commitment to continuing his research and writing. It is my sincere hope that he continues to explore and document the rich history of wildlife in India, translating his vast knowledge into works that can inspire a new generation of conservationists. His role as a mentor and historian is crucial in nurturing young minds passionate about conserving India’s natural heritage, ensuring that the legacy of both the wildlife and the conservation efforts to protect them continue to thrive.

As I boarded my plane to Abu Dhabi that evening, I couldn’t help but reflect on my experiences shared with Mr. Harsh Vardhan and Dr. Divyabhanusinh Chavda. There is no question that these gentlemen are heroes of India’s natural heritage. They are true legends on the brink of an era that must be carried forward. Their lives, deeply embedded in the Indian soil of conservation, remind each one of us that the torch of environmental stewardship is not only to be carried but also passed on. The footprints of their work—in the soft sands of the Rajasthan’s deserts and the dense foliage of India’s jungles—are deep and enduring. They have carried the mantle of responsibility with such humility, grace and fervor that stepping into their shoes may seem a daunting task for the next generation. Yet, this is a call to action for young conservationists across India: to rise and build upon the rich legacy of these remarkable figures. The path they have paved with their selfless commitment and passion is a beacon that guides us toward a future where conservation and respect for nature hold the keys to humanity’s survival and well-being. My message to the young generation of India – “let the stories of Mr. Harsh Vardhan’s deep connections with the community and Dr. Chavda’s scholarly pursuits inspire you to weave your own narratives of dedication and success in conservation”. The batons they carry are poised to be passed to young hands eager to mold a sustainable world, ensuring that the whispers of the past transform into the roars of future victories in the impending and difficult conservation battles to come. Jai Hind!

Leave a reply